this is a review of MOMA’s ongoing Matisse exhibition I wrote for the China Daily’s Sunday edition

Most people know Henri Matisse (1869-1954) for his elegant, simple shapes in bright, optimistic colors. However, the exhibition Matisse: Radical Reinvention, a collaboration between the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, reveals a very different Matisse: This is Matisse at his boldest and darkest.

The exhibition’s premise is that between his return from Morocco in 1913 and his departure for Nice in 1917, Matisse took his art in an assertive new direction. His paintings from this period are experimental, increasingly concerned about the act of art-making itself, as opposed to art as representation of its subject.

This casts Matisse as a proto-expressionist, anticipating the work of the likes of 20th-century great Jackson Pollock.

The more than 100 works on display feature scratched-out paint, leftover pencil marks, and blatant signs of reworking which Matisse made no effort to conceal. Perhaps the best way to understand what he was doing is to compare these experimental canvases to his sculpture.

The curators have cleverly juxtaposed these with his canvases. Matisse frequently worked on several pieces simultaneously.

In the first gallery, Blue Nude (1907) hangs beside Reclining Nude (1) (1907) – both works feature women in repose, with the painting clearly modeled on the sculpture.

In Blue Nude, the numerous layers of paint indicate Matisse’s fervent reworking of the figure. The effect is that of a bold display of the process of painting. You can see where Matisse corrected himself, where he has decided to shift the figure, sculpting the paint as he would the clay.

Reinvention also reveals a darker Matisse than the one in popular imagination – the self-doubt and perfectionism which drives the constant reworking is evident everywhere, and the gray and black tones echo the difficulties he grappled with in this turbulent period – the dark cloud of World War I was approaching, and his art was often poorly received.

Portrait of Olga Merson (1911) is a deeply ambiguous painting of a woman with whom the artist was obsessed. Merson kneels on the ground in what seems to be a perfectly pleasant, placid figure. However, a closer look reveals that the left half of her face has been scraped off, leaving a skittering of lines, as though the artist was simultaneously creating and un-creating. Two large black arcs cross her torso and hip. Are they lines of definition or cancellation?

The remarkable Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (1914) is even stronger in its use of radiating arcs, which seem to trace the energy of the subject rather than her form. Here Matisse has scratched out the arcs, and this lends the painting an energy and urgency – the result is powerful and textural.

One senses that Matisse was working with paint in a new way, layering it on, scraping it off, leaving the edges rough rather than polished.

To further underline the point, Matisse’s four monumental bronzes – Back I, Back II, Back III and Back IV – all female figures in more and more abstract form, range across the galleries, representing his move away from representation towards abstraction in this period.

Each of the Back sculptures was, in fact, a reworking of the plaster cast of the previous one, so here we can catch Matisse literally in the act of re-creation. A fascinating multimedia feature reconstructs this process, showing how the fleshy, realistic figure of Back I morphs into the monumental, almost architectural lines of Back IV.

If his Back series dominate the sculpture of the exhibition, then Bathers by a River (1909-10, 1913, 1916-17), hanging in pride of place in the final gallery, is its canvas counterpart.

This canvas was worked and reworked incessantly over nearly a decade, and serves as the focal point for the whole exhibition.

An informative video again reconstructs Matisse’s process – unearthed by an amazing slew of technological developments, including a delightful reconstruction of the 1913 state of the painting from photographs of Matisse’s studio by American photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn.

The new insights into Matisse’s process support the exhibition’s thesis, and the parallel observation in the Back sculptures: the naturalistic scene of 1909 gives way to four sharply divided panels, transforming the canvas from idyllic, Eden-like scene to something more modern and isolating.

However, it is The Piano Lesson (1916), also in the final gallery, that may be most intriguing.

In this large canvas, the painter’s son is depicted on the lower right at the piano. A female figure looks on from behind him. The whole left half of the canvas is a window, blocked out in gray, green and blue. The shaft of light that cuts through this piece is implied, and yet undeniable.

Matisse has captured a moment in time, and turned it into a monument.

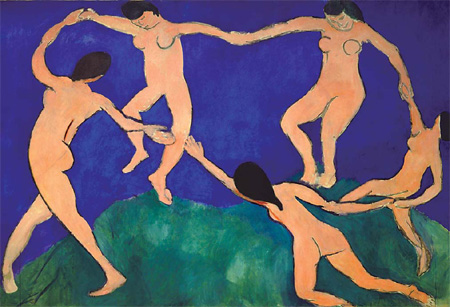

What is perhaps Matisse’s most famous work, Danse I (1909), conveniently hangs just one floor below at the Modern.

Its five rhythmic female forms, gracefully dancing in a circle, have become an icon of 20th-century art. However, it is important to remember that when it was first exhibited, it drew lashings of critical vitriol.

Some may find the curiously clumpy, unfinished hand of the figure on the left crude. However, in the light of the Modern’s latest exhibition, this choice makes more sense.

Even in his masterpiece, Matisse has displayed a willingness to reveal his sleight of hand, to lay bare his process in a frank and telling gesture. It is refreshing, and yes, surprisingly postmodern.

published at China Daily, 26th Sept 2010, Sunday.